“Akerlof’s new article takes off from Ellison’s theory of two dimensions of economics: hardness, and importance, with too much hardness and too little importance in equilibrium. Akerlof lists three reasons:

Reason 1: Place in the Scientific Hierarchy. Economists are proud of being more rigorous than anthropologists.

Reason 2: The Evaluation Process. Economists want to show how smart they are to get promoted.

Reason 3: Selection into the Profession. People who like hardness too much and importance too little are attracted to economics.

What we need to do is ask why a journal editor would prefer articles that have too much hardness and too little importance. Everybody likes importance, so really the issue is hardness, and why editors are willing to pick a hard unimportant article over a soft important one. Akerlof’s article is mostly about consequences rather than causes, so before I finish reading it, I’ll speculate on causes, something I was thinking of writing on anyway. I should be working on ostracism, immigration, and disgorgement, but I can’t resist writing on this.

A first issue is whether hardness is good or bad in itself. I think it is bad. Precision is good, and rigor, and those are part of hardness, but so is difficulty, which I think is purely bad. I am an advocate for what in my game theory book’s preface I call “no-fat” modelling, or “MIT-style” modelling, the kind Joe Stiglitz and Jean Tirole exemplify. These are mathematical models that try to be as simple as possible to convey a single point for each model. The model is a metaphor, you might say, but not a poetic metaphor full of detail and color but a Platonic form, an idea stripped down to its bare essentials. If you can assume prices are Hi/Lo and for just one good to make the point, you do that instead of letting them lie on a continuum from negative to positive infinity in a vector of prices for N goods. The model is still hard in the sense of rigor and clarity, but you make it as easy to understand as you can.

This is in contrast to what we might call the “mathematical economics” style. In that style, you try to build a model that is as general as possible. You don’t design it to make one point; you design it to comprehend as many points as you can. The result is much more difficult to understand. The model itself, however, tells you the conclusion in an application. You know from the theorem in the paper what happens when there are N goods with a continuum of prices; you don’t have to extrapolate from the 1-good two-price model.

That’s methodology, but love of hardness is also tied up with morality and psychology, and that, I think, is a key insight. Economics has since 1890 and Marshall been dominated by the two Cambridges, in East Anglia and New England. These places are notably leftwing nowadays, but historically they are the home of Puritanism, of Cranmer, Cromwell, Jonathan Edwards, and Cotton Mather. The real Puritans valued virtue and piety. We economists are also moralistic, but we value intelligence and hard work. Don McCloskey famously said that we have two moral dimensions of value: “Bob Solow sure is smart. And he’s a nice guy too.” Niceness isn’t relevant here, but I think we must add a third dimension, hard work. This isn’t quite diligence, because by “hard work” I mean doing something difficult, preferably with lots of effort– many hours, many mistakes along the way, lots of drafts, and much agony of spirit. Diligence allows simply plodding along, which is not good enough. We admire intelligence, and value it more highly than anything else, but we routinely deny tenure to intelligent people because they don’t work hard enough. I have heard of law schools and traditional Oxbridge valuing colleagues because they’re intelligent even though they’re lazy and unproductive, but in economics we frown on wasted talent and feel that the ex-assistant-professor has gotten the fate he deserves (especially if he’s not a nice guy either). We value hard work. It is no accident that Keynesianism cites digging holes and filling them in again as the metaphor for good policy.

Difficulty shows hard work. It isn’t that anyone in economics values an article being difficult to read. That is common in human society– there was a study that showed that the common man rates articles more highly if they’re more poorly written– but I don’t think economists are subject to that foolishness. We have enough self-confidence by now, I think, that Akerlof’s Reason 1 doesn’t apply much any more. Physics envy is ancient history, from back in the 1940’s. I think it’s ok with us if the peasants can read our articles and understand them– or, rather, we never think about that. It’s not like in academic Literature, where they want their articles to be hard to read so they look profound and they can’t be accused of just writing elegant book reviews in their academic journals. No– in economics, the people who value difficulty do it because they want to see articles that were difficult to write, and such articles generally are difficult to read. (Here, I might talk about what’s *really* difficult is to take something difficult to write and then rewrite it over and over until it’s easy to read and the reader wonders why nobody ever noticed such an obvious insight before. But that’s a step further.) So if an editor sees a submitted paper is hard, he thinks to himself, “This author really worked hard and I hope this is good enough that I can publish it.”

It’s isn’t just effort, though. The editor must also think, “This paper is about a really difficult idea. To write this required both intelligence and hard work. I really admire both those things, so I hope it also contains something at least a little bit important so I can publish it.”

In contrast, suppose the editor receives a paper that is important, but is not hard in the sense of difficult. For now, let’s suppose it is definitely hard in the sense of mathematical rigor, but the math is very easy. John Smith has noticed that simple algebra can do in two pages something that the literature has been doing with functional analysis in twenty pages. What is his reaction? First, he will recognize its importance. He will say to himself, “Wow: this is a great paper. It’s a joy to read, and it’s truly important.” Second, though, he will say, “But this is so easy. Does Smith really deserve a publication in my first-rank journal when he’s written something so short with so little effort? It seems unfair. Especially because I know Smith isn’t all that intelligent, and just got lucky or something when he thought of this.” The editor will put on a moral frown, because the paper does not show hard work.

A big part of the problem is Akerlof’s Reason Two, Evaluation. The editor, and most economists, are professors. We teach students. When a student submits a paper, unless it’s a graduate student who’s writing with an eye to publication, we don’t care about the paper’s quality, really. What we care about are two things, whether the student has learned from the experience of writing it, and how much the student knows about the class subject. We expect the paper itself to be rubbish, but it can still have made the student learn a lot and the many possibly levels of rubbishosity (say that five times fast!) convey student quality very well. We are looking for the inputs, intelligence and hard work, not the output, importance.

We don’t just evaluate students, though. We evaluate each other, constantly. We hire rookie PhD’s, we do annual reviews for the junior faculty, we figure out who can be poached away with outside offers, we do tenure reviews, we promote to full professor. This is a huge part of academic life, and, I imagine, must be a huge part of life for economists in business and government too. Personnel is policy, but even more it’s the key to the success of any organization. So we spend an inordinate amount of time on it, or, rather, an huge but ordinate amount. And when we do it, we look at the person’s papers. If he’s a rookie, the job market paper is overwhelmingly the most important item in getting a job. If he’s further along, we look at more papers. And here, as with the undergraduate term paper, our concern isn’t with paper quality, it’s with person quality. We all tell our PhD students how important it is that a job market paper show your intelligence and command of technique. We tell them that though later they can focus purely on importance, for a job market paper it’s prudent to slip in the fanciest techniques you can, so on the demand side the buyer can see he’s getting someone who will add to the department’s toolkit. Later, we say, you can strip out the fancy stuff from your dissertation when you put it into form suitable for publication, but showing off a little is a legitimate part of the job market, as long as you don’t pretend you’re not doing it and you really think the technique is necessary. As I say in the Aphorisms on Writing book chapter that I’m now revising into a book,

9.2 Purpose. When I was a student at MIT, Peter Temin told us that presentations

have three purposes:

(1) to tell something to people,

(2) to get comments, and

(3) to impress the audience.

Purpose (3) is perfectly appropriate to a job talk, but it tends to conflict with purposes (1) and (2).

Later on, a paper’s importance becomes more important, because we do value the ability to publish important papers as well as intelligence, if perhaps grudgingly. But even then, the evaluation process is about evaluating the person, not the paper.

Can someone shake that habit off when he becomes an editor? It’s hard to shake off habits of thought. The editor knows he ought to be publishing important papers, and if he stopped to think about it, he might agree that he should not think of his job as conveying signals of the writer’s quality by choosing what to publish. He should ruthlessly reject a paper that shows hard work and intelligence but is unimportant, even if the paper shows the author’s brilliance and diligence. He should happily accept a paper that is important but whose publication might lead the author’s department to award him tenure even though he’s stupid and lazy. The editor should not think, “Does the author deserve to have this on his vitae as a publication in a top-five journal?”, but “Will this publication confirm that my journal belongs in the top five?”.

But this takes us a to a separate problem: evaluating the evaluator. How can you tell who is a good editor? –by looking at how good the papers are that his journal publishes. Inevitably, most will be mediocre; that’s the definition of mediocre, after all. Some will be notably good, and some will be notably bad. The editor will yearn for the good, important, papers. But he will worry more about the bad, unimportant, papers that he will be blamed for accepting. His fear is that people will say, “The XX Journal. Hah! That’s the one that published that dumb Smith article back in 2018 when Jones was editor.” How can he avoid becoming Editor Jones? One way is to only accept papers by intelligent, hard-working authors. Their papers may lack importance, but at least they won’t have mistakes in them, and the utterly unimportant ones will just vanish quietly into obscurity rather than provoking laughter. Also, only publish papers that are difficult to read. If a really bad paper is also difficult to read, people won’t get more than two pages into it, so they won’t see how bad it is and you won’t get laughed at. On the other hand, if it’s difficult to read but important, people will struggle past and the paper will be a success, even if it might have been an even bigger success if it were easier to read. Finally, pretty much everyone will refrain from jeering at you for publishing unimportant but hard papers, even if they think your journal isn’t worth reading or citing. They say to themselves, “Editor Jones publishes really boring papers, but at least they’re professionally done and show lots of intelligence and hard work on the part of the authors.” That’s better than “How could Editor Jones have published something that’s both unimportant and easy!”

Of course, we’re wrong to give Editor Jones these incentives. It’s much worse to eat two-third of an egg and realize it’s bad and you’re going to start vomiting soon than to touch your tongue to an egg and realize it’s bad. But it’s irresistable to criticize him more for the verbal article with an idea that doesn’t come off than for the mathematical article that ends up not saying anything. Both articles are worthless, but the mathematical article is less obviously so.

I think signal jamming may enter in too, with respect to the editor’s incentives. You don’t become editor unless you’re very well respected. You’ve already published a lot of good articles; you’re tenured; everybody treats you very politely once you’re an editor; you are not only feared for your power, but loved for your generosity in putting your time into running a journal instead of working on your own research. So you’re sitting pretty. This is going to make you risk averse. Suppose you’re not really as good as people think. If you behave non-strategically, and just publish the articles you think are best, your low ability is going to be come evident from your big failures. If, on the other hand, you behave strategically by evaluating papers based on hardness rather than importance, no new information about your poor judgement will come out. People will stick with their priors— that you have pretty good judgement.

Psychology has to enter for this little model to work. As I just stated it, the editor with poor judgement will be found out. He will play it safe, and that will be observable, whereas the editor with good judgement will behave non-strategically and, in fact, the publication of a few lousy papers might serve to show that the editor has good judgement! Maybe the model is worth formalizing. I won’t do it here– though I can’t resist noting that the editor with good judgement would probably go even further and start signalling to destroy the signal jamming, being *more* risk-loving than he should be so as to really show he’s confident in his good judgement. But I will go on to add the psychological element: that in fact the editor himself does not know whether he has good judgement or not, and is very likely biased towards underestimating himself. Being able to write good papers is correlated with good editorial judgement, but by no means perfectly. Moreover, we are specialists in writing our papers, but an editor, even editor of a field journal, suddenly becomes a generalist, and has to think about topics he’s never thought about. That’s to say he’s uncertain about his judgement, but I’m pretty sure he’s biased downwards too. Academics are notoriously lacking in self-confidence about their mental capacity, just as beautiful women so often worry about their looks. We know we’re smarter than Joe on the Street– but am I as smart as the guy in the next office? I just became an editor– so do I deserve to be in the company of all those distinguished older scholars who are editors, and, in particular, how can I be as good as the guy I replaced? Many of us have Impostor Syndrome, where we fret over whether it’s all a big mistake and someone will discover how stupid we really are. So we are careful, and try not to burst the bubble– even though the bubble isn’t really there.

I might be wrong in this psychology. I’d value comment; it’s an empirical question, though one to address with interviews and anecdotes rather than regressions and diff-in-diffs. One can imagine editors with the opposite psychology. The day you’re sworn in as a United States Senator, you think to yourself, “How dare I enter the company of these 99 godlike men!” A year later, you think to yourself, “What are these other 99 idiots doing here?” It could be that editors are egomaniacs. It might be a good thing if they were. That would sweep away the problem of too much hardness, too little importance. They would be impatient with anything unnecessarily difficult and anything too hard for their giant brains to easily understand. They would take tremendous risks on papers that they thought everyone else might view as crazy, simplistic, or fatally flawed, but that they thought were pathbreaking. They’d often be completely wrong, because usually everyone else would be right, but that’s okay. Even more than assistant professors, journal articles are options. Their upside potential matters more than their downside risk. As Robert Fogel told me as a young visitor at Chicago in the 80’s, “Only your home runs count.” Most articles end up having no influence anyway, so it doesn’t really matter how bad they are. An article with a 90% chance of being fatally flawed and a 10% chance of being a classic is better than one with a 0% chance of being fatally flawed, a 100% chance of being read by 500 people and being cited 50 times, and a 0% chance of being a classic.

That’s where I would end if I wanted to be elegant. But before I forget, I want to note down some thoughts on Akerlof’s Reason 3, self-selection into the profession. This idea could use some development. Akerlof says,

One reason the profession seems to have gotten harder in recent years is a negative feedback loop. Biased rewards have caused the profession to intrinsically value hardness more; the intrinsic value placed on hardness has led to more biased rewards.

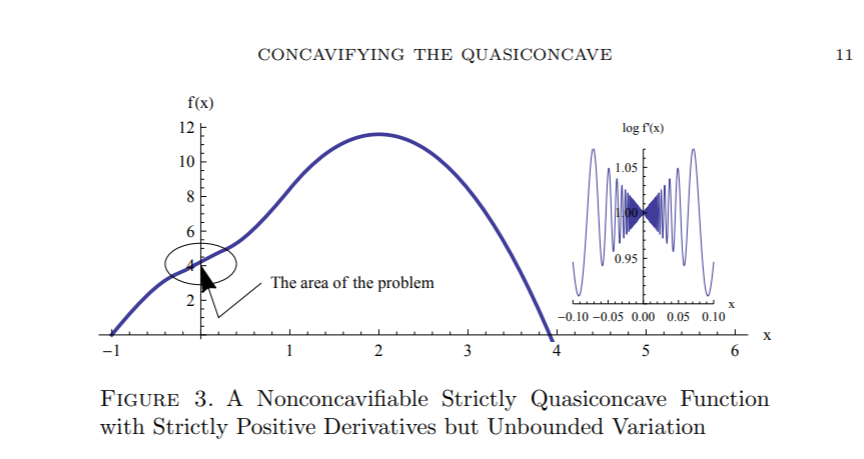

The more economics rewards hard papers, the more it attracts people who like to write hard papers and the more it repels people who don’t. That can be good as well as bad. If we value hardness optimally, then we will repel people who like to write papers that are too hard, and also repel people who like to write papers that are too soft. If we don’t, then we’ll reinforce the bad equilibrium. We are actually still at an interior solution. My geometer co-author and I had a very hard time getting our paper, “Concavifying the Quasi-Concave,” published, even though it has the coolest diagram I’ve ever had in any of my papers. Even the Journal of Mathematical Economics rejected it. Quite possibly that’s because it really did deserve a low Importance score, especially relative to its Hardness, but it did eventually get published in a math journal, The Journal of Convex Analysis. We had to change the economics version to math journal style, though, stripping out all the examples and the footnotes explaining odd math terms and shifting to the style Lakatos criticizes of “Theorem, Proof,” with no indication of the long path from idea to conclusion and all the zig-zags we had to take along the way. In any case, it’s an example of how mere math bravado won’t take you all the way, and a more mathematical person that myself might get discouraged by that.

Once the feedback loop is established, though, there’ll be a tendency to reach a fixed point, with all economists at the precise equilibrium level of hardness. It would be interesting to model reasons why that tendency would not reach the extreme result in terms of economists, even if the target hardness were reached in equilibrium and all articles had to be of at that target level. That is what the articles Akerlof cites, Akerlof & someone and Brock & Durlauf, are about, I imagine. It actually reminds me of a good covid-19 article on New York City I was reading today, New York City is dead forever. New York City elected a bad mayor, who messed up with covid-19 and messed up on crime. Sensible people flee the city. Sensible people are the ones who would vote against him. He will be re-elected, and more of the sensible people will leave. Eventually, perhaps, the material consequences result in foolish people changing their mind and reforming the government, but it’s difficult, because unlike with a poorly managed corporation, there’s no way someone can put at risk a large amount of capital, use it to gain power, reform the organization, and then make huge profits by reselling.

References.

Akerlof, George (2020) “Sins of Omission and the Practice of Economics,” Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. LVIII (June 2020).

Akerlof, George, and Pascal Michaillat. 2017. “Beetles: Biased Promotions and Persistence of False Belief.” NBER Working Paper 23523.

Altucher, James (2020) “New York City is dead forever,” New York Post, August 17, 2020.

Brock, William A., and Steven N. Durlauf. 1999. “A Formal Model of Theory Choice in Science.” Economic Theory 14 (1): 113–30.

Connell, Christopher & Eric B. Rasmusen, “Concavifying the Quasi-Concave,” Journal of Convex Analysis, 24(4): 1239-1262(December 2017) http://rasmusen.org/papers/quasi-short-connell-rasmusen.pdf or http://rasmusen.org/papers/quasi-connell-rasmusen.pdf.

Ellison, Glenn (2002) “Evolving Standards for Academic Publishing: A q-r Theory.” Journal of Political Economy 110 (5): 994–1034.

Frey, Bruno S. 2003. “Publishing as Prostitution? – Choosing between One’s Own Ideas and Academic Success.” Public Choice 116 (1–2): 205–23.

McCloskey, Donald (1995) “He’s Smart. And He’s a Nice Guy Too,” Eastern Economic Journal (Winter 1995).

Rasmusen, Eric (2001) Aphorisms on Writing, Speaking, and Listening, in Eric Rasmusen, ed., Readings in Games and Information, Blackwell Publishing (2001).

1 reply on “Hardness versus Importance in Economics”

[…] and Fact 13. How to Get a College Education 14.C. P. Snow, Good Judgement and Winston Churchill 15. Hardness versus Importance in Economics 16. Feeling Stupid in School and […]