To view the post on a separate page, click:

at

11/27/2007 09:48:00 AM (the permalink).

0 Comments

Links to this post

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, November 27, 2007

Downward Sloping Demand Curves for Stocks. Marzena Rostek presented "Frequent Trading and Price Impact in Thin Markets," (with Marek Weretka)today at Nuffield. It's a simple approach to downward-sloping demands for assets. Suppose there are a number of traders with CARA utility functions and stock returns are normal, so the traders care only about mean and variance. Each trader holds some portfolio of stocks. He would like to diversify, but if he puts some of his stock on the market, he has market power and will push down the price, since other people will have to be paid to hold more of that kind of risk. As a result, he will hold back some of the stock rather than diversify fully. Also, in way I do not fully understand this can explain splitting a trade up across periods. It is not for informational reasons-- there is full information in this model-- but because if I try to trade more of my stock in a period, I will drive down the price, keeping other people's quantity offered constant.

Wednesday, October 17, 2007

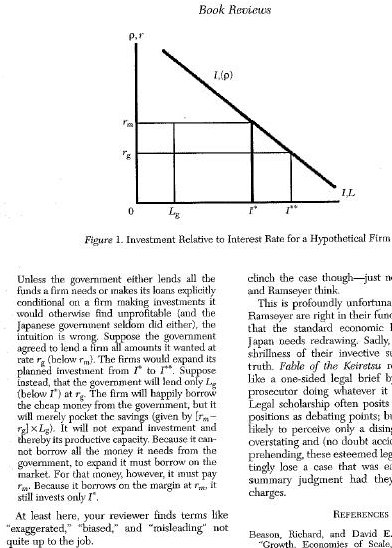

Negative Reviews and Inframarginal Subsidies for Investment. MR emailed me recently asking me to look at part of a review by RM of his recent book. As you can see, the review says the book's theory is "remarkable", quotes at length including a diagram, and then implies that the theory is wrong, without saying why. (Click here to read more.)

Labels: finance, Japan, price theory, reviews, writing

To view the post on a separate page, click:

at

10/17/2007 04:21:00 AM (the permalink).

0 Comments

Links to this post

![]()

![]()

I was equally puzzled, though. Maybe they should have used a numerical example. Suppose that a Japanese company invests 10 billion yen because it has to pay a 4% interest rate to borrow the money in the private financial markets and the last yen of those 10 billion invested would have a return of 4%. If they invested another billion yen, they'd only get 3%, having to go to worse projects, so they don't. But then the Japanese government offers to lend them the 10 billion at an interest rate of 2%. They eagerly take up the offer of course. But they still don't invest more than 10 billion. If they invested another billion by borrowing at 4% from the private sector, they'd still only get a 3% return and they'd lose money. Thus, government lending meant to increase investment won't succeed unless the government lends more than a private company was originally borrowing. Put more technically, this is an example of how inframarginal price changes have zero effect on real behavior.

I was equally puzzled, though. Maybe they should have used a numerical example. Suppose that a Japanese company invests 10 billion yen because it has to pay a 4% interest rate to borrow the money in the private financial markets and the last yen of those 10 billion invested would have a return of 4%. If they invested another billion yen, they'd only get 3%, having to go to worse projects, so they don't. But then the Japanese government offers to lend them the 10 billion at an interest rate of 2%. They eagerly take up the offer of course. But they still don't invest more than 10 billion. If they invested another billion by borrowing at 4% from the private sector, they'd still only get a 3% return and they'd lose money. Thus, government lending meant to increase investment won't succeed unless the government lends more than a private company was originally borrowing. Put more technically, this is an example of how inframarginal price changes have zero effect on real behavior.